Timeline

Nicholas Georgiadis’ work developed from his early years, starting from the time he was discovered by Dame Ninette de Valois at the Slade School of Art in 1955. She was looking for a theatre designer to work with the then young choreographer Kenneth Macmillan for the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet. Georgiadis went on to become one of the most important theatre designers of his generation with numerous productions for the Royal Opera House and the Royal Ballet in Covent Garden and a life long career as teacher of Theatre Design at the Slade School of Art. His life time collaboration with Rudolf Nureyev from the 1960s when Nureyev defected to the West and until Nureyev’s death in 1993 took Georgiadis all around the world with some of the most important ballet revisions since the time of Marius Petipa for famous classics such as Swan Lake, the Sleeping Beauty and the Nutcracker. His work for the stage was not limited to ballet alone but also encompassed opera and theatre where he broke new ground and where his productions were often described as masterpieces in the history of scenic design. His work was compared to that of Bakst and Benois from the Ballets Russes who dominated the first half of the twentieth century like he did the second half. His inspiration like theirs came primarily from being a painter, an artist who worked for the stage rather than the other way round and so every period is marked by achievements concurrently in his work on canvas as on stage for he treated the stage as a large canvas. His work for every period he himself identified is marked by important exhibitions and awards reflecting both his love for his art and his tireless spirit. Painting he wrote for me is like aspirin.

-

1955 – 1962: The Painting period

-

1962 – 1971: The Architectural period

-

1972 – 1980: Symbolism

-

1981 – 2001: Postmodernism

THE PAINTING PERIOD

During this period Nicholas Georgiadis used painterly colourful solutions for his work on the stage inspired by his own paintings that were influenced by Post War Art movements such as American Abstract Expressionism and European Art Informel as well as artists that preceded this movement such as Matisse, Raoul Dufy and Masson. Georgiadis was particularly interested in the work of his contemporaries such as Paul Klee, Mark Tobey, and Helene Vieira da Silva with their lyrical, mystical compositions. He was also inspired by the Post War landscape of London after the Blitz and London under reconstruction, the bombed facades, the windowless houses, the structures under construction, scaffolding and human interventions on the natural landscape. Kenneth Macmillan with whom he collaborated from 1955 for the Sadler’s Well Ballet and later the Royal Opera House with the support of Dame Ninette de Valois said that he admired the contemporary compositions of Georgiadis that matched the rhythms he looked for in his early choreographies. Nico brought vivid bright colours inspired by his native Greece onto the British stage that had not previously been seen there and influenced this way a generation of British theatre designers. As their first collaborations like Danses Concertantes (1955), the House of Birds (1955), Les Noctambules (1956), Agon (1958) dealt with either abstract themes or fairy tales with more sinister underlying themes, the use of colour and abstraction were able to match the demands of such works. Georgiadis was able to express geographical location or the time of the day or even some historical references through colour as well as mood and comment on the action symbolically. His gradual use of cut outs, side flaps, the illusion of depth through different means, classical and neoclassical reworkings and other sparse three dimensional props meant that the designs were never flat, nor uninteresting, mingled stillness with the movement on stage. Moreover, they created a sense of aura, mystery and mysticism characteristic of his paintings of that time as well. Nico was often compared to a magician or a conjurer that only few artists could achieve. As time progressed his palette became more tempered especially since the ballets undertaken between 1957/8 and 1960 became increasingly realistic and inspired by the Kitchen Sink movement such as the Burrow (1958) a story that resembled the diaries of Anne Frank and The Invitation (1960) that dealt with rape and the loss of innocence. Nico was always acutely aware of the demands of Macmillan who needed ample space for the dancers and a clear view of their bodies in anguish and expressing emotion and theatricality through physical movement. Macmillan worked with outstanding talented artists at that time such as Nadia Nerina, Maryon Lane, Anya Linden and Lynn Seymour to name but a few. They formed the famous diners club where there was vivid discussion, they inspired and taught one another. Georgiadis being older and very well educated played a key part in this. Macmillan and Georgiadis also travelled to New York to collaborate with ABT and the Stuttgart Ballet. Nico also worked in the theatre at that time with childhood friend Minos Volanakis for the Royal Court, Oxford Playhouse, the Bristol Old Vic and the Old Vic as well as the Royal Ballet Touring Company. He tackled Chekov, Jean Giraudoux, Shakespeare and Aristophanes. An exciting new career had began that showed immense potential and developed into something astonishing. Nico started teaching at the Slade school of Art where he had studied and won First Prize for Theatre Design and from 1958 run the Theatre Department jointly with Peter Snow. He never stopped exhibiting his paintings and theatre designs in prestigious shows at the Redfern Gallery and Annely Juda Fine Art to name but a few important gallery spaces.

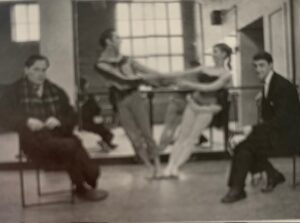

(images 1, 3) Nicholas Georgiadis, The Invitation (1960), score Mathias Seiber, choreography Kenneth Macmillan, The Royal Ballet’s Lynn Seymour and Christopher Gable as the Boy and the Girl.

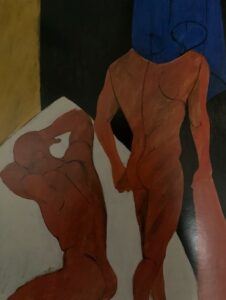

(image 2) Nicholas Georgiadis, Inside the Eyes (1961), Mixed Media on Board.

© Nicholas Georgiadis. All Rights Reserved 2024.

The architectural period

This period of Georgiadis’s career was characterised by more realistic works that required a gradually different approach to create a sense of vraisemblance or verismo. Colour was therefore combined with more three dimensional solutions to tackle reality in combination with a variety of new techniques such as form, pattern, texture and collage. When one looks at the painting activity of Georgiadis during this time, it is evident where his own personal inspiration came from. Large increasingly geometrical canvases evolved from Painterly Abstraction of the previous years. From 1963 onwards Georgiadis spoke of his interest and influences from American and later British Post Painterly Abstraction. He was not interested in the Hard Edge strands of such movements however but in geometry, architectural ambiguity and the aesthetics of colour. The religious mysticism of the previous canvases was now being replaced by a sensual kind of mysticism stemming from different forms and tones of colour reacting together, first in tight vertical structures, then in forms that extended horizontally in more loose, simpler compositions and later still in strictly geometrical compositions with illusions of false perspective always using techniques combining collage and painting. Towards the end of this period trompe l’oeil techniques were used and the spray gun replaced the paint brush and collage to comment on reworkings of classical architectural forms or reinvent heavy duty man made interventions on the natural landscape. These paintings clearly influenced the works on stage of Georgiadis during this time indirectly from opera, to ballet, to theatre and film. Although Georgiadis never carelessly transferred his canvases on stage, always sensitive to the unique demands of each individual work and seeking innovation and constant evolution, inspiration from them was inevitable for he was a painter working on the stage, always seeing it as a large canvas from his own personal perspective within the context of his time. His designs also influenced his canvases but never to make them more theatrical as he said, only more active and this symbiotic relationship helped create some important works that are now considered masterpieces in the repertory of classical ballet and opera such as Kenneth Macmillan’s Romeo and Juliet (1965), Peter Potter’s Aida (1968) and Volanakis’s Les Troyens (1969). In some cases these were so ahead of their time that it took years for them to be accepted, embraced and celebrated as masterpieces.

Pattern, form, collage as well as colour or the lack of it aided the understanding of the main issues of the works such as seen in Macmillan’s Las Hermanas (1963) or Noureev’s Casse Noisette (1968). In the latter work the whole ballet was perceived as a large encrusted present wrapped up in wallpapers, painted doilies, and linked to children and toys from the 19th century adhering to both the story by Dumas and the music by Tchaikovsky. The leafy patterns on the costumes of the main characters linked Clara and the Nutcracker soldier to Drosselmeyer and the party guests of the Stahlbaum household. This interpretation by Georgiadis highlighted Clara’s dreams and nightmares and foregrounded her psychology, as representative of the inner desires and fears of an adolescent girl’s mind and going from the specific to the universal and from the classical to the contemporary. During this period Georgiadis identified different concerns when designing for opera, ballet or the theatre.

Ballet had to respect the time the story was written but at the same time pay heed to the time of the musical composition. Moreover there was a need to allow plenty of space for the dancing so structures had to be pushed back even if they became less naturalistic. In the theatre by contrast structures could be more natural but also needed to be sparse because the words were the most important element. Here the time and views of the author were paramount to be communicated through the costumes and designs. In opera, the designer could fill the stage with more realistic constructions and details could be added to costumes and sets because the language of the librettos often being foreign, the spectator had more time to notice detail and the eye to wander. Music and the times of the composer were the starting point of the designs for opera even if the story alluded to earlier times. Georgiadis being an innovator however and constantly challenging himself dared to sometimes transfer the works to more contemporary settings to avoid kitsch and repetition as long as these reflected equivalent values to those of the original conception of the works. Both his Swan Lake for Kenneth Macmillan in 1969 and his Casse Noisette for Nureyev in 1968 were set in a Napoleonic setting, Rothbart appearing like Napoleon with a large military cape and plumed hat, whilst Drosselmeyer an aged Nelson. Siegrfried’s mother looked like a young Queen Victoria from the 1840s. Sir John Tooley former Director of the Royal Opera House commented on the immense imagination and flexibility in Georgiadis’s designs, in overcoming every obstacle and demand made of him, big or small and in bringing to the stage real works of art. His interpretations were never a pastiche or enamoured with the past however and sometimes departed from historical accuracy for the sake of theatrical demands. In Romeo and Juliet for example the chapel is Byzantine in inspiration and not part of the overall Italian Renaissance setting, heightening the dramatic tension. Moreover Georgiadis was greatly inspired by painting and architecture of the times he set his works in as well as by his own painting and artistic sense. What resulted always bore his own unique and recognisable signature. Architectural structures during this period were not only grand and impressive, some of the most awe inspiring works ever to be seen on stage, but practical and ingenuous, with as few scene changes as possible, either opening to reveal more elements within, or adding parts to existing structures so as to allow the natural flow of the unfolding stories seemingly effortlessly.

.

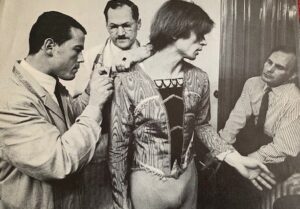

(images 1, 2) Nicholas Georgiadis, Romeo and Juliet film (1966), Juliet’s Ante-Room, score Sergei Prokofiev, choreography Kenneth Macmillan, Margot Fonteyn and Gerd Larsen as Juliet and her nurse.

(image 3) Nicholas Georgiadis, Stele (1965), Mixed Media on Board.

© Nicholas Georgiadis. All Rights Reserved 2024.

Symbolism

In the years that followed Nico declared that he had ceased to paint and that he had reached an impasse with this painting. This was not altogether true for between 1972 and 1979 he produced a series of wonderful prints, collages and drawings of pivotal importance to his later development in painting that greatly influenced some of his greatest masterpieces on the stage such as Manon and Mayerling. Moreover in the frustration he was experiencing he was not alone. Abstraction and pure painting in general seemed to have reached an impasse with the ready made, pop art, text and conceptualism taking over and doing away with the painterly and the individual stream of consciousness. It seemed that few were the artists that continued to paint and he was drawn to those like Hockney and particularly Kitaj who painted figuratively albeit in a new way combining painting with ideas of the ready made. Nico’s interest in geometry had not altogether eclipsed either, but now he used figures in conjunction to geometrical shapes, as pseudo ready-mades in interesting and mysterious compositions that mixed collage with historical, painterly and religious reference and allusion. The first ones were monochromatic and gradually some scarce colour was introduced. They had the impression of being like parables, but were in fact influenced by Renaissance allegorical painting, Hieronymus Bosch and religious texts like the Bible and the Koran. Furthermore, they embraced Symbolist and Metaphysical Art and also alluded to Ingres and his painting Oedipus Explaining the Enigma of the Sphinx, bringing an element of mysticism that characterised and evolved from his previous work on canvas. A persistent theme of symbols of power and authority in anthropomorphic and later zoomorphic form such as Angels, Hawks, Lions and pointing hands were initially placed in triangles and other shapes spiralling around and pointing to movement at the top of the pictures. They were sometimes accompanied by text taken out of religious scriptures. At the bottom of such pictures an outline of a fallen man with multiple arms and legs or a mourning dark figure alluded to a fallen man or a figure in distress and agony. The ground below was indicated by zig zagging patterns of lines like symbols of thunderbolts. Everything was undermined by fragmentation, fracturing, incompletion and fiction accentuated by arrows indicating constant movement and transience. The statues representing the Angels were broken, headless with arrows for wings whilst human torsos were missing limbs or multiplied them, gradually resembling and mirroring the angels they were supposed to be contrasted to. The surrounding landscapes were reduced to lines, circles and patterns that reminded of Kenneth Noland’s circular colour field paintings and were additional comments of human interventions on the natural landscape. The suggestions of seismic patterns transformed from symbols of power to those of rupture, fracture and weakness, turning the drawings into transient, ever moving spaces of meaning and meaninglessness where one thing could be at once itself as well as its direct opposite, this way effacing difference. These were themes that would later evolve and develop into Nico’s larger all colourful impressive canvases that emerged from the early 1990s onwards.

The symbolic nature of these drawings point to connections with the theatrical solutions that were given by Georgiadis during the same time. During this time Nico described his design solutions as those belonging to Selective Realism since conventional realism was replaced by concise, symbolic and more modern, universal scenic design combined with descriptive, detailed, rich and historical costumes. Often the structures used on stage were singular and were kept on stage throughout the production presenting a direct commentary from the designer to his audience. In Manon for example a cyclorama of rags appeared even in the brothel scene commenting in an ingenuous way to the dire economic situation in pre-Revolutionary Paris where fortunes could be made and lost in a day due to galloping inflation, gambling and corruption. Beggars, pimps and prostitutes rubbed shoulders with the aristocracy and the wealthy, as seen in the very demise of Manon. In the last scene the rags transform into weeds at the Louisiana swamp where Manon dies penniless in the hands of her beloved Des Grieux haunted by nightmares of her past life and the impossibility of her love affair in life. On a practical level the rags being concise allowed plenty of space for the dancing, made the action move fast without any hindrance and pointed not only to the actions, characters and conclusion of the story but also to the inner mind of Manon in turmoil torn between greed, power and love. The rags being a universal symbol of poverty, but also of fate reminiscent of Georgiadis’s drawings similar in shape to the multiple triangles, arrows or hands, they also transformed into the direct opposite, the mind of Manon itself, responsible for her own predicament and torn between opposing values. The costumes themselves detailed, rich and historical, were inspired by 18th century French book illustrators like Gravelot and some were direct references like the Ratcatcher and the girl in the trousers. The different textures, materials and colours contrasted the elegant Paris Salon society and the decadent brothels with the fetid atmosphere evoked by the beggars in rags and the prostitutes at the harbour of New Orleans oozing disease, malnutrition and death. Wigs, jewels, furs, bows, rich fabrics and gold trimmings contrasted with the greenish, brown and washed out colours of the vagrants. Colour also served a symbolic purpose, Manon appearing first in white and pale blue on the way to the convent a picture of innocence and hope, then in a beautiful black dress at the brothel (black being the most expensive colour to buy in 18th century Paris) denoting her new status and wealth having chosen to be a kept woman and later returning to a bedraggled greenish putrid revealing dress with hair cut short to signify her fall from grace and exile to Louisiana. A similar scenic solution to Manon was used in other ballets such as Mayerling in 1978 where the denouement at the forest in Mayerling was hinted at from the outset by panels remaining on stage throughout the ballet that pointed at once to a forest whilst symbolising at the same time the troubled mind of Prince Rudolf himself driven to insanity and suicide: the tree branches looked at once like part of the forest but also like veins or arteries inside his diseased head whilst darkness and the colour black became a harbinger of death and inner turmoil.

© Nicholas Georgiadis. All Rights Reserved 2024.

Postmodernism

In the last twenty years of Georgiadis’s career, the theatrical solutions he gave his work for the stage were comparable to the previous period in that they were highly symbolic but there was a difference in scale. In his desire to bring the works closer to a modern audience and to make them more comprehensible, he made them increasingly abstract, universal and less descriptive even in the case of opera, where previously the stage had been filled with architectural structures. This facilitated movement especially in the case of ballet and made the pace of the action faster and more cinematic. Costume design itself became more acutely symbolic and more modern assisting in the freedom of movement. Even though Georgiadis was highly respectful of the time of artistic creation of the works as well as the time of their musical composition, the designs still worked on multiple temporal levels concisely, and in the cases where they were transferred to a more modern milieu to avoid cliché, they were not carelessly transferred to the present time, but found a more contemporary and innovative equivalent that was similarly selective. One can identify three radical ways that Georgiadis tackled the works of this period that can be seen as having associations with the postmodern: Minimalist or no scenery combined with descriptive costume that carried modern or futuristic references as well as historical ones, such as appeared in the ballets: Manfred (1971), Orpheus (1982), the Tempest (1982) and the Prince of the Pagodas (1989). The second was by presenting an emblematic, symbolic centrepiece or main idea that rotated opened and closed, but in effect stayed the same juxtatposed with innovative costumes blending several historical and theatrical periods of time at once, as in Raymonda (1983), Anatol (1987), the Sleeping Beauty with Macmillan (1987), La Belle au Bois Dormant with Nureyev (1989), La Clemenza di Tito (1988), Adrianna Lecouvreur (1992) and Romeo and Juliet (1999). The third and final method used was by bringing the scenery and costumes forward to a more contemporary setting altogether but without losing the references to the past and the origins of the original stories, scripts or plays, as happened with Casse Noisette set in 1910 (1985), La Traviata set in the 1920s (1995), Antigone (1999) and the Bacchae set in modern times but with allusions to Ancient Greece (2001).

This period saw the acute foregrounding of fiction on stage through painterly as well as non realistic three dimensional structures, whether it be through the use of a repeated vocabulary of symbols of power or in the creation of semi realistic and semi fictive scenes. Examples can be found in the drapes, flags, spheres, horses, clouds and obelisks prominent in La Clemenza di Tito (1988) and the Sleeping Beauty (1987), or in the postcard image of the Eiffel Tower blown up on stage next to a mirror image of Alfreddo in La Traviata and in the toy landscape of moving castles in the Prince of the Pagodas half way between reality and the mind of their heroines. The mysterious scenic design was combined with the creation of hybrid figures on stage through dual masks or the emphasis of blending human actors and dancers on stage with dolls and mannequins, like in the two headed masks of Orpheus or the monkey court in the Prince of the Pagodas and the Salamander Prince half lizard and half man. The repetitive undermining of reality and the blurring of boundaries, whether temporal, spatial, or existential was not a coincidence but was thoroughly intentional. It was particularly prominent in Georgiadis’s extraordinary vibrant large canvases that appeared from the early 1990s right to the end of the artist’s life and fuelled his inspiration for the stage with working ideas from the early 1980s. The aim was to convey universal messages about the human condition, the fiction of our existence, the opposing forces of our outer civilised world and our hidden, troubled, animalistic and often dark interior inhabited by fears, desires, anxieties, struggles and contradictions.

The canvases were made within the wider context of Postmodern ideas of the time and alluded to painting through the ages from the Renaissance to modern times with direct and indirect references. Gericault’s the Raft of the Medusa was reproduced by Georgiadis in his own modern interpretation of the Raft. Ingres’s Oedipus and the Sphinx made a return in some of his works on paper and so did the enigmatic monkey from Tiepolo’s The family of Darius before Alexander the Great, bringing light relief but also laughing at humans or being symbol of the subconscious mind. Like ready made images, the paintings showed representations of repeated imagery from past but also from modern times such as those of soldiers, cowboys, men in suits and naked men that populate the Western modern world through the media, film, books, magazines and the television. These were blended with ancient statues from classical times and religious symbols as well as zoomorphic images. Egyptian pharaohs, sphinxes, cloaked and mourning figures with religious undertones and creeping all powerful plants became mysterious symbols of past, lost and incomplete knowledge. Georgiadis often quoted the metaphysical paintings of the early twentieth century artists such as Carra and de Chirico as inspirations. Fractured bodies and reverted images of falling men or men lying down like broken statues harked back to Georgiadis’s prints from the previous period and recalled nightmares or recurring dreams of the so called Western civilised world. Scenes of heightened tension, shock and anxiety, such as volcanic eruptions and men jumping up from their seats gave an added element of the psychological traumas of modern times but also of the fears and anxieties of our subconscious minds. Were these images of our inner worlds represented here or our exterior worlds or possibly both and neither? Open reading of the paintings was left to the spectator, with the themes of seeing, witnessing, acting or watching as a spectator and the complexities of seeing as common themes and titles of the works. Differences, boundaries and dividers merged into one and were questioned in a timeless and endless movement that refused conclusion or resolution These highly enigmatic paintings blend space, time, human identity and reality to keep asking deep philosophical questions about who we are, who we were and who we will be, nothing and everything, good and bad, powerful and powerless all at once.

© Nicholas Georgiadis. All Rights Reserved 2024.

Texts by Evgenia Daniel. Website Design by Harry Daniel © Evgenia Daniel. All Rights Reserved 2024.